Kant’s Life: The House on Prinzessenstraße

“After knocking, and having been invited to enter with a cheery ‘come in’, one pushes open an utterly simple and shabby door into an equally miserable Sanssouci.”

Und so drang man durch eine ganz einfache, armselige Tür in das ebenso ärmliche Sanssouci, zu dessen Betreten man beim Anpochen durch ein frohes „Herein“ geladen wurde...

— Hasse [1804]

Kant arranged the purchase of a house at 87-88 Prinzessinstraße near the end of 1783 – its previous owner was the widow of Johann Gottlieb Becker, the painter whose portrait of Kant [see] was hanging in Kanter’s bookshop. Kant moved in no later than 22 May 1784, and by July had paid off the mortgage and owned it free and clear.[1] The house was due north of the west end of the castle, about half-way between it and the Paradeplatz.[2] Jachmann [bio] described it as being on a quiet side street with little else than foot traffic, even though it was in the center of town [Jachmann 1804, 179]. It was also near Hippel’s [bio] house,[3] and the two quite likely dined at the same neighborhood pub – the “Caffee- und Gasthaus Zornich” – which was just around the corner from Kant’s house, on the Junker Straße; Kant did not have a working kitchen until 1787 (after which he always held luncheons in his own home) [cf. Stark 1994a, 107-8]. Kant was also neighbor to Friedrich Karl Ludwig von Holstein-Beck [bio], whose house at Junker Straße 13-14 was directly next to Kant’s, and from whom we have an important set of physical geography notes.

May 22 would have been too late to begin holding his lectures for summer term (these began for Kant at 7 o’clock Monday morning, April 26, to some 100 students attending his logic lecture), but he may well have changed locations as soon as he was moved in; by the very latest he was lecturing in his own home beginning WS 1784/85.

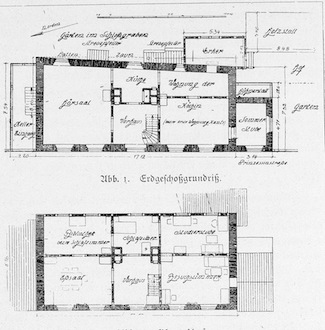

The house had two floors and an attic, and lined up roughly on a north-south axis, so that one faced east (and a bit south) when entering the front door. As one entered the front door (in the middle of the house), the lecture room occupied the left side (or north end) of the first floor (with two windows facing the street, and a single window on the opposite wall with a view of the gardens and castle). The kitchen was east of the front hallway, and the cook’s apartment was on the right side of the ground floor. Directly above the lecture hall, on the second floor, were the dining room (with two windows facing the street to the west) and on the back side of the house a room used as Kant’s library, with his bedroom directly above the kitchen, situated between the library to the north, and his study to the south; the library had two windows facing the gardens and castle, the bedroom one window.[4]

On the right hand side, above the cook’s apartment, was a salon for greeting visitors (with two windows facing the street) and Kant’s study in the back, with two windows offering a view of the neighboring gardens and castle, as well as the Löbenicht church (on whose steeple Kant would apparently fix his gaze while in deep thought – see the Wasianski piece, below). As Puttlich [bio] noted in his diary (for 30 April 1785): “Kant has not decorated his rooms at all, Rousseau’s picture alone hangs above his writing desk.”[5] In the attic lived his servant Martin Lampe [bio] [Jachmann 1804, 180].

The lecture room was a square roughly six meters on the side, and clearly too small for the 80-100 students that he was recorded as hosting. Jachmann reports (in his 4th Letter) that Kant’s “lecture room, especially at the beginning of the semester, could not hold all the auditors for his public lectures, and quite a few would have to occupy an adjoining room or the hallway” [1804, 33].

A few of the readings discuss the unfortunate afterlife suffered by Kant’s house, and it was eventually torn down in 1893 to make room for a neighboring store. Jachmann tells us that the house was purchased immediately after Kant’s death for use as an inn, complete with billiards and a bowling lane. Thirty years after that a dentist by the name of Döbbelin bought the house (August 31, 1836), where he both lived and practiced his dentistry, and eventually installing a plaque in Kant’s memory over the entrance[6] (this would have been the time that the colored engraving (right) was made, and perhaps the plaque is the small dark area visible above the front door. After this the house was turned into a shop, which it remained until 1893 [Kuhrke 1924, 16-18].

Jachmann

Kant’s former student and early biographer – Reinhold Bernard Jachmann – offers a brief description of Kant’s house at the beginning of “Letter Sixteen,” and then closes with a plea that the house be better preserved now that Kant is gone:

“During the last seventeen years of his life, Kant lived in his own house. While located in the middle of the city near the castle, it is on a small side street through which carriages seldom pass. The house itself, with its eight rooms, was comfortably furnished for his way of life. On the lower floor, his lecture hall was in one wing and [180] the apartment of his old cook in the other. One wing of the upper floor had a dining room, his library, and his bedroom, and the other his visiting parlour and his study. His servant lived in a small attic room. The study lay to the east and had a free view over several gardens. It was a pleasant retreat where the great thinker could indulge his ideas calmly and undisturbed. He would have been even more satisfied with the study had he been able to open the windows more often in summer, but this was prevented by the incessant singing of the prisoners in the jail of the nearby castle. He often complained to Hippel about this spiritual outburst of boredom, but there was no changing it.

The furnishings of his rooms was entirely simple. There was a mirror only in the parlor and in the dining room. In the rest there were some tables, chairs, [181] and a small sofa. The white walls were wholly undecorated. His study contained, other than his writing table, also a commode and two tables covered with writings and books. On the wall hung Jean Jacques Rousseau. The other household appliances were just as simple. It was decent and tasteful, although designed for only his small housekeeping and a few guests. It passed through my hands several times whenever a cook was replaced, at which times I was especially happy about the simple furnishing of his household.

In the years when Kant could still rely on his old servant, who later became very weak, almost everything stood under his supervision, managing the house, courtyard, and cellar. In the evening Kant handed out the grocery list for the following noon and his Lampe ensured that everything was done [182] according to his master's wishes. Kant had the greatest confidence in his honesty, and he deserved it. But in the end, Lampe's old age made it necessary to retire him with a lifelong annuity and to choose another servant for the remaining years. […]”

“[188] […] Rings are being woven from the silver hair of the deceased and I hear they are selling well; but I suspect the same will happen with Kant's hair as happened with the relics of saints, and soon there will be more Kantian hair rings among the public than Kant ever had individual hairs in his whole life. It is striking that, in the midst of this unprecedented enthusiasm for the great man, that no patriot has come forth to buy the house in which the wise man lived and from which he proclaimed his wisdom to the world, and to put it to some use worthy of the great man. Instead it will become an inn, [189] with a billiard table and a bowling alley. I have nothing against billiards or bowling, but it seems offensive to me that this should happen in the very house where Kant once taught philosophy.” [Source: Jachmann 1804, 179-82, 188-89]

Kant’s Destitute Sans-Soucci

Johann Gottfried Hasse (1759-1806)[bio] was a professor of oriental languages at Königsberg and a regular table guest of Kant’s during the last three years of his life. Near the beginning of this 1804 biographical sketch of Kant we are offered a description of visiting the philosopher, whose study is compared (unfavorably?) with the palace – a mini-Versailles – that Friedrich II (“the Great”) had built outside Potsdam between 1745-47, and that he called Sanssouci — French for “no worries.”

“On approaching his house, everything announced a philosopher. The house was a bit antique. It stood in a street that was walkable but was not much used by carriages, with its backside bordered by gardens and the castle moat, as well as the back buildings of the many hundred-years-old castle with its towers, its prisons, and its owls. In spring and summer, however, the area was quite romantic – except he did not really enjoy it (it wasn’t his garden that lay on the side, where there was no window) but simply saw it. Stepping inside, one experiences a peaceful quiet, and one might [5] even think the house was uninhabited, except for the smells from the open kitchen and the barking of a dog or meowing of a cat, darlings of his female cook (who performed, as Kant put it, entire sermons for them). Upon climbing the stairs one encounters the servant busy setting the table, but pass through this very simple, unadorned and somewhat smoky hallway into a larger room that was the fancy parlour, but which showed little splendour. (What Nepos said of Atticus[7] – elegant, not magnificent – was certainly true of Kant.) There was a simple sofa, [6] some chairs upholstered in linen, a glass cabinet with some porcelain, a secretary that held his silverware and his cash, and a thermometer. These were all the furnishings, which covered a part of the white walls. And so one arrived at a quite simple, poor-looking door to that equally destitute sans-souci, into which one was invited by a cheerful “come in” as soon as one knocked. (How my heart pounded, the first time I did this!) The entire room breathed simplicity and quiet isolation from the noises of the city and the world. There were two common tables, a simple sofa, some chairs, including his study-seat, and a chamber pot, which left enough space in the middle of the room to get to the barometer and thermometer, that Kant often consulted. Here the thinker sat on his wooden half-circle chair, like on a tripod,[8] either still at his work-table or else already turned toward the door, because he was hungry and was eagerly waiting for his guests to arrive. But he sat how and when he wanted, even if he didn't always match the tense expectations of those meeting him for the first time. His face was cheerful, his eye lively, his expression friendly – and when he spoke, he really did sound oracular and was enchanting.” [Source: Hasse 1804, 4-6]

Kant at his Window

From Wasianski’s [bio] 1804 biography of Kant:

“At six o’clock he sat down to his desk, which was just a wholly ordinary table, and read until dusk. At this time, so conducive to thought, he would meditate on his reading, if it was worth that, or else he would sketch out what he would say in his lectures the following day, or else work on something for publication. Then he would take up his station by the stove, be it winter or summer, from which he could see, through his window, the Lobenicht [30] steeple.[9] He would look at this while meditating, or better put, he would rest his eyes on it. He could not emphasize enough how beneficial this was for his eyes, how suitable was the distance of the object for this. His daily gazing in the twilight accustomed his eyes to this, for eventually some poplars in the neighbor’s garden grew to such a height as to hide the steeple, and this left Kant unsettled and disturbed in his meditation; he wanted the poplars pruned. Fortunately the owner of the garden was a considerate fellow who loved and respected Kant, and so he sacrificed for him the boughs of his poplars, making the steeple visible once more so that Kant could once again meditate undisturbed.” [Source: Wasianski 1804, 29-30]

Kant’s Dusty Walls

In his Autobiography, Scheffner [bio] recounts one of his many visits to Kant’s study:

“I’ve always believed in keeping a good apartment, as well as order in my study, so my rooms never looked like student rooms; everything was done up as best as possible and well dusted. In some things I am a regular order-pedant, who is annoyed, for instance when fish bones on the plate are not set to the side. [37] Even in someone else’s room it bothers me to see the chairs not put back in place as soon as they’re done being used. Kant thought otherwise on this point. The walls of his study were gray from dust and the smoke from his morning pipe. Once, while listening to his conversation with Hippel, I drew my finger along the wall to reveal the white paint underneath. Kant said, ‘Friend, why are you ruining that antique rust? Isn’t a wallpaper that comes about on its own better than one purchased?’” [Source: Scheffner 1816, 36-37]

After Kant

The following piece appeared anonymously a few months after Kant’s death. The middle paragraph was set in verse, and is here offered in literal translation. (Mühlpfordt [1970, 273] attributes this anonymous essay to J. G. Hasse.)

“Kant’s house is sold, sold to a restaurateur. Of all the wealthy, rich, and very rich inhabitants of my hometown, not one of them thought to buy this house and put it to a more noble use in honored memory of the philosopher! There, let me say it – not to you, since your feelings are my own – but to those money-men, who can only see if you set the barn ablaze – the nominal sum for which the house was sold could have erected a monument to our compatriot that those better places would envy and will always envy, like the “Eisleber” Lutherans. And does Kant deserve less than Luther?

"Luther began. / One ended, One. No more metaphysical conclusions / piling up into towers of truth, no more news of the supernatural / pulled down from above. The One accepted hard pressed reason, full of his own strength. / “What can reason, as a special source of knowledge, accomplish for us?” – This he determined, like none before. / Kant, Immanuel Kant, when justice is done, the moral will becomes universal in the world, thanks be to your efforts!”

What might we have done, had a worthy emeritus professor lived in this house? With the hall where the professor taught, his picture above the podium from which the philosophical reform of the earth was brought forth; with the room in which he worked; with his writing desk upon which the texts written for eternity were sketched out and developed? Here is the youth, serious in the exhaltation of his mind, being led into the lecture hall where each year a speech is given in memory of the philosopher; here the tested youth is rewarded with the applause of his betters – what hopes! what prospects for the future! – and now we hear the clinking of beer glasses and the bacchanalian songs rising from the very hall where once youth and men had entered with reverence – and it’s visited more now than ever!!! And here, where Kant spent his entire, great life, where those eternal ideas took shape – now the earned nickels are tallied. Above the door, instead of a marble plaque with the words Here lived Kant, we find: Au Billiard Royale – and no one suspects or punishes[10] the disgrace of this desecration!” [Source: Zeitung für die elegante Welt, Leipzig, 21 July 1804]