Chronological List of Kant’s Writings

1747

Living Forces [translations]

Gedanken von der wahren Schätzung der lebendigen Kräfte und Beurteilung der Beweise derer sich Herr von Leibniz und andere Mechaniker in dieser Streitsache bedienet haben, nebst einigen vorhergehenden Betrachtungen welche die Kraft der Körper überhaupt betreffen (Königsberg: Martin Eberhard Dorn, 1746), xxiv, 240 pp. [AA 1: 3-181; AA3 1: 1-158] “Thoughts on the True Estimation of Living Forces.” Translated by Jeffrey B. Edwards and Martin Schönfeld in Watkins [2012, 11-155].

In this first publication, a book-length manuscript, Kant attempts to reconcile the competing doctrines of physical force as developed by Descartes (where force = mv) and by Leibniz (where force = mv2). The book was dedicated to J. C. Bohl [bio], a professor of medicine at Königsberg. Not much is known about Bohl, and rather less about the relationship between him and Kant; but that Kant would dedicate his first publication to a professor of medicine (and not, for instance, to Knützen [bio], who was traditionally understood to be Kant’s primary mentor) is remarkable. Borowski claims it was done to thank Bohl for various kindnesses shown to Kant and his parents when he was a child [1804, 194].

According to Borowski, Kant began working on this book in 1744 [1804, 164]. Printing began in 1746 (with financial help from Kant’s uncle Richter, a shoemaker), after it had been submitted to the university censor,

Kurd Lasswitz, in his Introduction to the Academy edition reprint [AA 1: 521-22], reports that Kant’s essay was presented to the dean of the philosophy faculty (during SS 1746, Johann Adam Gregorovius, Senior), who entered it into the records:

“Censurae Decani scripta sunt oblata sequentia: … . (b) Immanuel Kandt Stud: plen: Tit: Gedancken von der wahren Schätzung der lebendigen Kräffte etc.”

As required by law, all printed matter published in Königsberg required prior censoring by the appropriate faculty of the university.

and ‘1746’ is the year that appears on the title page. It was not until 1747, however, that Kant added the preface, the dedication, and §§107-113A and §§151-56, completing the book as it now stands, with the dedication dated “22 April 1747” – Kant’s 23rd birthday. The whole was not published until 1749, however, appearing in the summer.

In a letter of 23 August 1749, sent with a copy of the book and a request for a review, Kant notes that

“the printing of this little work was finished only in this year, although it was begun in 1746, as indicated on the title page“ [AA 10: 1].

The recipient of this letter was thought to be Albrecht von Haller, who was a leading naturalist of the day, and this is supported by a second letter Kant sent that day that was addressed to an equally famous mathematician, Leonhard Euler [unavailable for the Academy edition, this letter is published in Schöndörffer/Malter 1986, 925-26]. The letter’s closing paragraph closely matches the closing paragraph of an anonymous book review published in the Franckfurtische Gelehrte Zeitungen (Num. 41, 14 Nov 1749, pp. 501-3) [PDF].

Kant’s inaugural publication received some critical notice: reviews in the Franckfurtische Gelehrte Zeitungen (Num. 41, 14 Nov 1749, pp. 501-3) [PDF], the Göttingische Zeitungen von Gelehrten Sachen (Num. 37, 13 April 1750, pp. 290-94) [PDF], the Latin Nova Acta Eruditorum (March 1751, pp. 177-79) [PDF]), and a witty dismissal by G. E. Lessing:

K. unternimmt ein schwer Geschäfte,

Der Welt zum Unterricht.

Er schätztet die lebendigen Kräfte,

Nur seine schätzt er nicht.

English: “Kant undertook the difficult business of educating the world. He estimated the living forces, without first estimating his own.” [Lessing, Werke, 1: 47; first published in Das Neueste aus dem Reich des Witzes (July 1751).]

Kant’s personal copy, now lost, had been in the possession of F. W. Schubert. In an editorial note to a passage in the text of his 1839 edition, Schubert wrote: “In my copy, which Kant himself had used, was written in the margin by his hand and with the firm handwriting typical of the period from 1750-70 […]” [Rosenkranz/Schubert 1838-42, 5: 107]

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 1: 1-282].

1754

Rotation of the Earth [translations]

“Untersuchung der Frage, ob die Erde in ihrer Umdrehung um die Achse, wodurch sie die Abwechselung des Tages und der Nacht hervorbringt, einige Veränderung seit den ersten Zeiten ihres Ursprungs erlitten habe und woraus man sich ihrer versichern könne, welche von der Königlichen Akademie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin zum Preise für das jetztlaufende Jahr aufgegeben worden.” The actual title used in the newspaper is simply a reference to the prize essay question: “Untersuchung der Frage, welche von der königl. Academie der Wissenschaften zu Berlin zum Preise vor das jetztlaufende Jahr aufgegeben worden.” Kant provides a German translation of the essay question in the second paragraph of the text. Wochentliche Königsbergische Frag- und Anzeigungs-Nachrichten (1754), #23 (June 8, pp. 2-3) and #24 (June 15, pp. 2-3). [AA 1: 185-91; AA3 1: 159-66] “Examination of the Question whether the Rotation of the Earth on its Axis, by which it Brings About the Alternation of Day and Night, has Undergone any Change Since its Origin, and How One Can be Certain of This, which was set by the Royal Academy of Sciences in Berlin as the Prize Question for the Current Year.” Translated by Olaf Reinhardt in Watkins [2012, 159-64].

This essay was published in two successive issues of a Königsberg weekly newspaper. It is the first of four essays that Kant wrote in response to questions posed by the Royal Academy in Berlin. The others are Optimism (1759), the Prize Essay (1764), and Progress in Metaphysics (1793). The last of these was not published in Kant’s lifetime, and there is no evidence that Kant ever submitted the 1754 and 1759 essays to the Academy. The Academy announced the question on 1 June 1752 with essays to be submitted by 1754, but on June 6th of that year the deadline was pushed back to 1756. See a brief list of Academy prize questions. Kant argues that the rotational speed of the earth is gradually slowing as a result of the frictional effects of the tides – a claim that actually turns out to be true.

At the end of this essay, Kant promises a longer work with the title Cosmogony, or Essay on the Origin of the Cosmos, the Formation of the Heavenly Bodies, and the Causes of their Motion, derived from the general laws of motion of matter, in accordance with Newtonian theory [Kosmogonie, oder Versuch, den Ursprung des Weltgebäudes, die Bildung der Himmelskörper und die Ursachen ihrer Bewegung aus den allgemeinen Bewegungsgesetzen der Materie, der Theorie des Newton gemäß, herzuleiten] – which did in fact appear the following year, although under a different title, and in that work, Kant refers to this essay: “I shall save this solution for another occasion because it is necessarily related to the topic set for the prize by the Royal Academy of Sciences in Berlin for 1754.” [AA 1: 287; Reinhardt transl.].

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 81-90].

Age of the Earth [translations]

“Die Frage, ob die Erde veralte, physikalisch erwogen.” Wochentliche Königsbergische Frag- und Anzeigungs-Nachrichten (1754), ##32-37 (Aug 10 - Sep 14). [AA 1: 195-213; AA3 1: 167-85] “The Question, Whether the Earth is Ageing, Considered From a Physical Point of View.” Translated by Olaf Reinhardt in Watkins [2012, 167-81].

This essay was published sequentially in six successive issues of a Königsberg weekly newspaper.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 91-120].

1755

Theory of the Heavens [translations]

(anon.)

While published anonymously, Kant had already anounced this book [AA 1: 191] at the end of his signed, two-part essay on the “Rotation of the Earth” (Wochentliche Königsbergische Frag- und Anzeigungs-Nachrichten, #24, 15 June 1754), although the title at that time read: Kosmogonie, oder Versuch, den Ursprung des Weltgebäudes, die Bildung der Himmelskörper und die Ursachen ihrer Bewegung aus den allgemeinen Bewegungsgesetzen der Materie, der Theorie des Newton gemäß, herzuleiten.

One impetus for the change of title may have been Kant’s coming across the title of the recently published German translation of Buffon’s Allgemeine Historie der Natur nach allen ihren besondern Theilen abgehandelt [Original: Histoire naturelle générale et particulière] (my thanks to Werner Stark for bringing this to my attention).

Allgemeine Naturgeschichte und Theorie des Himmels, oder Versuch von der Verfassung und dem mechanischen Ursprunge des ganzen Weltgebäudes, nach Newtonischen Grundsätzen abgehandelt (Königsberg and Leipzig: Johann Friederich Petersen, 1755), 200 pp. [AA 1: 217-368; AA3 1: 187-324] “Universal Natural History and Theory of the Heavens, or Essay on the Constitution and Mechanical Origin of the Entire Universe, treated in accordance with Newtonian Principles.” Translated by W. Hastie in Hastie [1900]; by Stanley L. Jaki in Jaki [1981]; by Olaf Reinhardt in Watkins [2012, 191-308].

The academy edition is based on the 1755 edition. Changes made to the text by Kant for the selection reprinted by Gensichen (1791 – see below) are noted in the Sachliche Erläuterungen [AA 1: 547-57]. This practice was also followed in the Reinhardt translation.

This 200 pp. book explains the origin of the physical universe using Newtonian mechanics, thus removing God from the direct design of the universe (although still requiring a divine guarantor of the natural laws). This was Kant’s “nebular hypothesis” that Laplace independently formulated and published in 1796, and with whose name it is often associated.

Kant’s book appeared in March 1755, but soon after this the publisher went bankrupt and his inventory was seized [Dreher 1896, 174]. Consequently this work – dedicated to the King and carrying with it the hopes for some literary fame for the young author – scarcely enjoyed a public viewing in Kant’s day, and was little known outside of Königsberg; Although two reviews appeared that year: in the Jenaische gelehrte Zeitungen (14 June 1755; pp. 355-59 [PDF]) and the Hamburgische Freye Urtheile und Nachrichten (15 July 1755, pp. 429-32 [PDF]). In Königsberg, the book’s publication as well as the identity of its author was announced in the Wöchentlichen Königsbergischen Frag- und Anzeigungs-Nachrichten (1 May 1756). Goldbeck noted in 1781 that “this work is one of his first writings and has only lately become recognized” [1781, 248].

Later scholars arrived at conclusions similar to and independently of Kant – Johann Lambert in 1761 and Pierre-Simon Laplace in 1796. In response to Lambert’s publication, Kant offered a sketch of the book’s general argument in his 1763 Only Possible Argument (see the Seventh Reflection, entitled “Cosmogony“, of Pt. II), and near the end of the “Preface” to that book he tried to correct the public record with the following footnote:

“The title of the book is Allgemeine Naturgeschichte […]. This work, which has remained little known, cannot have come to the attention of, among others, the celebrated J. H. Lambert. Six years later, in his Kosmologische Briefe 1761, he presented precisely the same theory of the systematic constitution of the cosmos in general, the Milky way, the nebulae, and so forth, which is to be found in my above-mentioned theory of the heavens, the first part, and likewise in the preface to that book. […] The agreement between the thoughts of this ingenious man and those presented by myself at that time almost extends to the finer details of the theory, and it only serves to strengthen my supposition that this sketch will receive additional confirmation in the course of time” [AA 2: 69; Walford transl.]

Kant’s neighbor and future publisher Friedrich Nicolovius encouraged Kant to consider republishing this book, suggesting that he ask “Herr Bode in Berlin or else Herr Hofprediger Schulz in Königsberg” whether they would want to take on the work of preparing an updated edition (letter to Kant, 20 September 1789) [AA 11: 88]. Kant eventually wrote to Bode (2 September 1790) [AA 11: 203-4] who declined the invitation (9 September 1790) [AA 11: 203-5], after which Kant turned to his younger colleague and close friend, J. F Gensichen [bio] – see his letter of 19 April 1791) [AA 11: 252-53] – who proceeded to publish a selection, as an appendix to a translation into German of three essays by William Herschel: Über den Bau des Himmels, transl. into German by George Michael Sommer (Königsberg: Nicolovius, 1791), 204 pp. The Kant selection is found on pp. 163-204, and is preceded by a brief explanation written by Gensichen; see Vorländer [1924, 1: 104, 2: 86]. Borowski [1804, 78] includes this reprint in his list of Kant’s publications (#44), noting that Gensichen published it on Kant’s instructions, but also that Kant had added some emendations.

See also Kant’s letter to Biester (8 June 1781) [AA 10: 272-74] and Lambert’s introductory letter to Kant (13 November 1765) [AA 10: 51-54].

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 1: 283-520].

On Fire [translations]

Meditationum quarundam de igne succincta delineatio. Published posthumously in: Rosenkranz/Schubert, Immanuel Kant’s sämmtliche Werke, 5: 233-54 (1839). [AA 1: 371-84; AA3 1: 326-65] “Concise Outline of Some Reflections on Fire.” Translated by Lewis White Beck in Beck [1992, 16-33] and in Watkins [2012, 311-26].

Commonly referred to as De igne. Presented to the Philosophy Faculty at the university at Königsberg on 17 April 1755 as partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Magister degree. Only doctoral dissertations of the three higher faculty were required to be published, and De igne was never published in Kant’s lifetime, upon whose death the 12 sheet large 4° manuscript was given to the university library, where it was found in 1838 by Schubert and published for the first time in the Rosenkranz/Schubert collected works [cf. Lasswitz’s introduction at AA 1: 562].

New Elucidation [translations]

Principiorum primorum cognitionis metaphysicae nova dilucidatio (Königsberg: Johann Heinrich Hartung, 1755), ii, 38 pp. [AA 1: 387-416; AA3 1: 366-449] “New Elucidation of the First Principles of Metaphysical Cognition.” Translated by J. A. Reuscher in Beck [1992, 42-83]; by David Walford and Ralf Meerbote in Walford [1992, 5-45].

Commonly referred to as Nova dilucidatio. Presented to the philosophy faculty at the university at Königsberg as (the 18th century equivalent of) his Habilitationsschrift and defended on 27 September 1755 as Kant’s disputatio pro receptio [glossary], required for obtaining the right to offer lectures at the university.

This was the first of three public Latin defenses in which Kant served as the principal, and is briefly described in the Professors pages. It is also Kant’s first purely philosophical work. Wolff and Crusius both come under discussion: Wolff’s determinism is defended against Crusius [AA 1: 401-5], but Kant rejects Wolff’s commitment to a single metaphysical principle (for Wolff: the principle of contradiction) and of his and Leibniz’s proof of the principle of sufficient reason, and Kant follows Crusius in replacing Wolff’s “sufficient ground” with a “determining ground” [AA 1: 393]. Kant also replaces Wolff’s single principle with two: sucession and co-existence.

Kant rejects the ontological argument for God’s existence (at the time a mainstay of natural theology) on the basis that existence as an idea cannot guarantee existence in reality (later captured with the claim that ‘existence is not a predicate’; see Only Possible Argument, 1763). He will further develop this idea in his Negative Magnitudes (1763), where he introduces the notion of real grounds (in contrast to logical grounds). The upshot is that logical analysis is never adequate for grounding existential claims – to put the same in Kant’s later terminology: such claims are always synthetic, not analytic.

While rejecting the ontological argument, Kant sketches-out a proof that God’s existence is a necessary ground for the possibility of anything at all [AA 1: 395], a proof that he develops more fully as the Only Possible Argument.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 121-72], followed by a German translation [pp. 173-248].

1756

Earthquakes 1 [translations]

“Von den Ursachen der Erderschütterungen bei Gelegenheit des Unglücks, welches die westliche Länder von Europa gegen das Ende des vorigen Jahres betroffen hat.” Wochentliche Königsbergische Frag- und Anzeigungs-Nachrichten (1756), #4 (Jan 24) and #5 (Jan 31). [AA 1: 419-27; AA3 1: 451-60] “On the Causes of the Earthquakes, on the Occasion of the Calamity that befell the Western Countries of Europe towards the End of Last Year.” Translated by Olaf Reinhardt in Watkins [2012, 329-36].

This and the following two essays were occasioned by the Lisbon earthquake of 1 November 1755 that destroyed over half of the city and killed tens of thousands of its citizens. The science of plate tectonics lay far in the future, and Kant’s scientific explanation of the cause of the earthquake [AA 1: 423-25] was entirely false, but Kant’s primary point was that the earthquake was to be understood in wholly physical terms – being neither an affront to God’s goodness and power, nor an example of God’s punishment – and that the proper response to such events should be in better urban planning [AA 1: 421].

Earthquakes 2 [translations]

Geschichte und Naturbeschreibung der merkwürdigsten Vorfälle des Erdbebens, welches an dem Ende des 1755sten Jahres einen großen Teil der Erde erschüttert hat (Königsberg: Johann Heinrich Hartung, 1756), 40 pp. [AA 1: 431-61; AA3 1: 461-91] “History and Natural Description of the Most Noteworthy Occurrences of the Earthquake that Struck a Large Part of the Earth at the End of the Year 1755.” Translated by Olaf Reinhardt in Watkins [2012, 339-64].

Kant announced his intention to publish this more detailed account of earthquakes (“a more detailed treatise will be published in a few days”) at the end of the 2nd installment of his first essay (31 Jan 1756); the actual publication was announced on 11 Mar 1756 in the same newspaper. Unlike the first and third essays, which appeared in a local newspaper, this essay was printed as a pamphlet. It was approved by the censor on 21 February 1756.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 1: 521-74].

Earthquakes 3 [translations]

“Fortgesetzte Betrachtung der seit einiger Zeit wahrgenommenen Erderschütterungen.” Wochentliche Königsbergische Frag- und Anzeigungs-Nachrichten (1756), #15 (Apr 10) and #16 (Apr 17). [AA 1: 465-72; 493-501] “Continued Observations of the Terrestrial Convulsions that have been Perceived for Some Time.” Translated by Olaf Reinhardt in Watkins [2012, 367-73].

Kant’s final essay on earthquakes, again appearing as installments in two successive issues of the local newspaper, appears to have been occasioned by a desire to contest certain recent physical accounts of earthquakes (viz., that the cause lies with the alignment of the planets, or with the moon).

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 249-60].

Physical Monadology [translations]

Metaphysicae cum geometria junctae usus in philosophia naturali, cuius specimen I. continet monadologiam physicam (Königsberg: Hartung, 1756), 16 pp. [AA 1: 475-87; AA3 1: 502-37] “The Employment in Natural Philosophy of Metaphysics combined with Geometry, of which Sample One Contains the Physical Monadology.” Translated by Lewis White Beck in Beck [1992, 92-106]; by David Walford and Ralf Meerbote in Walford [1992, 51-66].

Presented to the philosophy faculty at the university at Königsberg on 23 March 1756 as partial fulfilment of the requirements to become an associate professor (Knutzen's position had been vacant since his death in 1751). This was the occasion for Kant’s second public Latin defense, which took place on April 10th and is briefly described in the Professors pages.

This work explicitly declares Kant’s interest in reconciling Leibnizian-Wolffian rationalism with Newtonian mechanics, the principle point here being their differing accounts of space: the physical monads or atoms of rationalism are indivisible, yet Newtonian space is infinitely divisible. Kant resolves this with a “dynamic” conception of the atom.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 261-84], followed by a German translation [pp. 285-316].

Theory of Winds [translations]

Neue Anmerkungen zur Erläuterung der Theorie der Winde (Königsberg: Johann Friedrich Driest, 1756), 12 pp. [AA 1: 491-503; AA3 1: 539-52] “New Notes to Explain the Theory of the Winds, in which, at the same time, he Invites Attendance at his Lectures. Königsberg, the 25th of April, 1756.” Translated by Olaf Reinhardt in Watkins [2012, 375-85].

In this brief essay, which also served as a Lecture announcement for SS 1756, Kant gives a new and correct account of the cause of coastal and trade winds, as well as the cause of seasonal monsoons. This is material that would have been included in his new course on physical geography.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 317-35].

1757

West Winds [translations]

Entwurf und Ankündigung eines Collegii der physischen Geographie nebst dem Anhange einer kurzen Betrachtung über die Frage: Ob die Westwinde in unsern Gegenden darum feucht seien, weil sie über ein großes Meer streichen (Königsberg: Johann Friedrich Driest, 1757), 8 pp. [AA 2: 3-12] “Plan and Announcement of a Series of Lectures on Physical Geography, with an Appendix Containing a Brief Consideration of the Question, Whether the West Winds in our Regions are Moist because they Travel over a Great Sea.” Translated in part as Appendix 1 in Bolin [1968, 224-33]. Translated by Olaf Reinhardt in Watkins [2012, 387-95].

Lecture announcement for SS 1757.

The manuscript was received by the censor by April 13, 1757 [AA 2: 455].

This essay primarily concerns Kant's lectures on physical geography, which he will give for the second time this semester: a preliminary discussion of the subject (pp. 3-4), a short sketch of the physical geography lectures (pp. 4-9), a brief paragraph noting the other lectures on offer that semester (pp. 9-10), and then the discussion of the winds (pp. 10-12).

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 336-50].

1758

Motion and Rest [translations]

Neuer Lehrbegriff der Bewegung und Ruhe und der damit verknüpften Folgerungen in den ersten Gründen der Naturwissenschaft (Königsberg: Johann Friedrich Driest, 1758), 8 pp. [AA 2: 15-25] “New Doctrine of Motion and Rest, and the Conclusions associated with it in the Fundamental Principles of Natural Science, while at the same time his lectures for this semester are announced, the 1st of April, 1758.” Translated by Olaf Reinhardt in Watkins [2012, 399-408].

In this brief pamphlet Kant argues against the Newtonian concept of absolute motion and absolute rest, as well as against the concept of inertial force in a resting body that resists other bodies that might push against it. The pamphlet concludes with a one-paragraph lecture announcement for SS 1758.

Reprinted in Rink [1800, 7-23], Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 7-23].

1759

Optimism [translations]

Versuch einiger Betrachtungen über den Optimismus von M. Immanuel Kant, wodurch er zugleich seine Vorlesungen auf das bevorstehende halbe Jahr ankündigt. Den 7. October 1759 (Königsberg: Johann Friedrich Driest, 1759), 8 pp. [AA 2: 29-35] “An Attempt at Some Reflections on Optimism by Immanuel Kant, also containing an announcement of his lectures for the coming semester. 7th October 1759.” Translated by David Walford and Ralf Meerbote in Walford [1992, 67-83].

Lecture announcement for WS 1759/60.

This essay began as a response to the Prussian Academy of Science prize essay question (announced for 1755); its publication occurred one day after the habilitation defense of a new lecturer, Daniel Weymann [bio], a follower of Crusius, who thought Kant’s defense of Leibnizian optimism was directed at himself. Weymann promptly published a rejoinder that Kant chose to ignore (see Kant’s letter to Lindner, 28 October 1759, and Kuehn’s discussion of the affair [2001, 122-4]). See a brief list of Academy prize questions.

Borowski [1804, 58-59] reports that Kant, in his later years, wished for this essay to be suppressed – perhaps, as Nauen [1992] suggests, because it made Kant sound too much like a Spinozist.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 351-61].

1760

Funk [translations]

Gedanken bei dem frühzeitigen Ableben des Herrn Johann Friedrich von Funk, in einem Sendschreiben an seine Mutter (Königsberg: Johann Friedrich Driest, 1760), 8 pp. [AA 2: 39-44/ed. Paul Menzer] “Thoughts on the Premature Death of Mr. Johann Friedrich von Funk.” Translated by Margot Wielgus, Nelli Haase, Patrick Frierson, and Paul Guyer in Frierson/Guyer [2011, 3-8].

This is an open letter written to the grieving mother of a favorite student of Kant’s, Johann Friedrich von Funk (1738-1760), who apparently died of exhaustion. In this brief writing, Kant reflects on the contingency of life, on how our lives rarely turn out as expected, and that death then “suddenly ends the entire game” [AA 2: 41]. He submitted the letter to the philosophy dean (C. A. Christiani) on 4 June 1760.

L. E. Borowski [bio] knew Funk well, and in the annotated catalog of Kant’s publications included in his 1804 biography of Kant [1804, 59], suggests that this letter was written at the request of Funk’s Hofmeister, in the belief that Kant’s words would help console the grieving mother.

This student should not be confused with the instructor of law, Johann Daniel Funk [bio], who had married Knutzen’s widow, and was a close friend of Kant’s during his early years as a Magister.

Reprinted in Rink [1800, 24-33], Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 24-33].

1762

False Subtlety [translations]

Die falsche Spitzfindigkeit der vier syllogistischen Figuren erwiesen (Königsberg: Johann Jakob Kanter, 1762), 35 pp. [AA 2: 47-61] “The False Subtlety of the Four Syllogistic Figures Demonstrated by M. Immanuel Kant.” Translated by David Walford and Ralf Meerbote in Walford [1992, 89-105].

This pamphlet was written “in a few hours” [AA 2: 57] as a Lecture announcement for WS 1762/63; this would have been in September 1762, as the semester began October 11.

The brief essay argues for the unoriginal claim that the Aristotelian syllogistic logic contains redundancies, although we do find Kant focusing on the nature of judgment and its relation to concepts.

Reviewed by Resewitz in Briefe, die neueste Litteratur betreffend, 22: 147-58 (letter 323; May 2, 1765).

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 1: 575-610].

1763

The Only Possible Argument [translations]

Der einzig mögliche Beweisgrund zu einer Demonstration des Daseins Gottes (Königsberg: Johann Jakob Kanter, 1763), xiv, 205 pp. [AA 2: 65-163] “The Only Possible Argument in Support of a Demonstration of the Existence of God.” Translated by Gordon Treash in Treash [1979]; by David Walford and Ralf Meerbote in Walford [1992, 111-201].

This book bears a “1763” publication date, but was in fact published mid-December of 1762. See J. G. Hamann’s letter of 21 December 1762 to Friedrich Nicolai, which notes that the work had “just left the press.” [Briefwechsel, 2: 181] Walford estimates that Kant finished the essay in October, so just after finishing False Subtlety [Walford 1992, lvii, lix].

The “only possible argument” for God’s existence is based on the possible existence of anything else. Kant first rejects Descartes’ ontological argument on the grounds that it assumes existence is a [real] predicate, which it is not – a point Kant already made in the New Elucidation (1755) – and then he proceeds to develop an alternative a priori argument from the concept of possibility: The possibility of anything must be grounded in some real existent, and what exists prior to such possible existence would have to be a necessary existence that we call ‘God’.

In the Seventh Reflection of Pt. II, entitled “Cosmogony,” Kant offered a sketch of the general argument in his 1755 Theory of the Heavens.

A positive review of this book by Resewitz or Mendelssohn The identity of the review’s author has been widely debated; see Sgarbi [2025, 76-81]. in Briefe die neueste Literatur betreffend, 18: 69-102 (letters 280-81; April/May 1764) made Kant’s name known throughout Germany.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 2: 55-246].

Negative Magnitudes [translations]

Versuch den Begriff der negativen Größen in die Weltweisheit einzuführen (Königsberg: Johann Jakob Kanter, 1763), viii, 72 pp. [AA 2: 167-204] “Attempt to Introduce the Concept of Negative Magnitudes into Philosophy.” Translated by David Walford and Ralf Meerbote in Walford [1992, 207-41].

Submitted to the academic censor on June 3, 1763, “along with an appendix containing a hydrodynamic exercise” (as qtd. in Walford/Meerbote 1992, lxi). There is some reason to believe this was composed the previous year. In The Only Possible Argument (1763) we find logical and real ground being used, but not introduced or defined as such. For instance: “[T]he actuality by means of which, as by means of a ground, the internal possibility of other realities is given, I shall call the first real ground of this absolute possibility, the law of contradiction being in like manner its first logical ground.” [AA 2: 79]. This gives us some reason to believe that its composition (October 1762, according to Walford [1992, lix]) followed that of the Negative Magnitudes. The appendix has been lost.

Kant opposes using the mathematical method in metaphysics, and criticizes Wolff’s theory of judgment for obscuring the real and conceptual (or “logical”) orders, collapsing the relation between a real ground and its effect into the analytic subject-predicate relation of a logical ground and its consequence. At the end of the essay, Kant raises for the first time his concern with causality (i.e., how we are to understand the efficacy of real grounds): “How am I to understand that something exists because something else exists?”

Reviewed by Resewitz in Briefe, die neueste Litteratur betreffend, 22: 159-76 (letter 324; May 2 and May 9, 1965).

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 1: 611-76].

1764

Beautiful and Sublime [translations]

Beobachtungen über das Gefühl des Schönen und Erhabenen (Königsberg: Johann Jakob Kanter, 1764), 110 pp. [AA 2: 207-56] “Observations on the Feeling of the Beautiful and the Sublime.” Translated by John T. Goldthwait in Goldthwait [1960]. Edited by Günter Zöller, translated by Paul Guyer in Zöller/Louden [2007, 23-62].

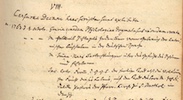

Completed by 8 October 1763, the submission date to the philosophy dean for censoring,

The entry of Kant’s censored book in the registry [need catalog data]; image courtesy of Martin Walther.

Kant wrote this during the summer recess at a house in Moditten owned by his friend Wobser, a forester.

Further editions (in Kant’s lifetime): 2nd (Königsberg: Kanter, 1766), 3rd (Riga: Hartknoch, 1771), 4th (Graz: Andreas Leykam, 1797). The work also appeared in two collections: vol. 2 of I. Kants sämmtlichen kleine Schriften, nach der Zeitfolge geordnet (4 vols., Königsberg and Leipzig: [no publisher indicated], 1797-98) and vol. 2 of Immanuel Kant’s vermischte Schriften (3 vols.; Halle: Renger, 1799).

Kant’s own copy Kant’s interleafed copy was given to Kant’s publisher Nicolovius (18 September 1800), and from Nicolovius’s estate 1836 auction found its way to Schubert, who passed it on to Reicke and then university library [Schubert 1857, 54-55; Warda 1903, 544], where it was lost or destroyed during World War II. Fortunately photographs had been made and are available in the university library at Göttingen. Gerhard Lehmann’s transcription of Kant’s marginalia were published in 1942 [AA 20: 3-181]. was interleaved, and the remarks that he wrote here in 1764-65 can be found at AA 20: 3-181, and in the more useful edition by Rischmüller [1991]; a selection of these remarks have been translated into English and included in Guyer et al. [2005, 3-24]. It is unclear why he thought to write these remarks in this book: they generally do not concern the text alongside which they are written, nor do they appear to have been intended as revisions or additions to the text, since subsequent editions were relatively unrevised, and certainly did not reflect these remarks.

The title of this popular publication suggests a work on aesthetics (and thus as an early version of the first half of Kant’s 1790 Critique of Judgment), but the content is more in line with portions of what would become his popular lectures on anthropology (beginning with WS 1772/73). Other than the three essays on earthquakes, this was Kant’s first publication aimed at a general reading audience, and was the work by which Kant was best known at the time. As an example of this book’s popularity: Conrad Friedrich Ziegler, a Hofmeister supervising the study of two young noblemen at Erlangen, having learned of the offer of a professorship from that university to Kant [more], wrote in a letter to Kant (3 Jan 1770) that he and his two charges would be most pleased to offer him lodging until he was able to find a more suitable residence, and after listing Erlangen’s many virtues, also mentioned that Minister Carl Friedrich, Freiherr von Seckendorf, the Kurator of the university, was quite enamored by Kant’s Beobachtungen über das Gefühl des Schönen und Erhabenen, and on the basis of that book had asked to have Kant called to the university [AA 10: 86].

On the Adventurer Komarnicki [translations]

(anon.) “Raisonnement über einen Abentheurer Jan Pawlikowicz Zdomozyrskich Komarnicki.” Königsbergsche Gelehrte und Politische Zeitungen, #3, 10 February 1764. [AA 2: 489] “On the Adventurer Komarnicki.” Translated by Claudia Schmidt in Zöller/Louden [2007, 63-64].

This brief paragraph of text appears in the Academy edition only in the editor’s introduction to the “Essay on the Maladies of the Head,” although it was included alongside Kant’s other published writings in Hartenstein’s first [1838-39, 10: 3] and second [1867-68, 2: 209] editions of Kant’s writings, as well as in the editions by Rosenkranz/Schubert [1838-42, x.1, 198-99] and Kirchmann [1870-91, 8: 65]. Borowski includes it in his list of Kant’s publications: “1764. (N. 17.) Raisonnement über einen Abentheurer Jan Pawlikowicz Zdomozyrskich Komarnicki" [1804, 63], and in Appendix 1 reprints the article from the Königsbergsche Gelehrte und Politische Zeitungen: text by Johann Georg Hamann (Kant’s acquaintance and the newspaper’s editor at the time), followed by Kant’s brief remarks [1804, 206-10]. Adickes [1896, 14] and Warda [1919] also list this item.

Hamann offers some details of Jan Pawlikowicz Zdomozyrskich Komarnicki, a fifty-year-old religious fanatic known as the “goat prophet” because of his many goats (along with sundry cows and sheep), who during the winter of 1763-64 was travelling near Königsberg and became the object of considerable public attention. He was accompanied by an eight-year-old boy, whom Kant viewed as a kind of noble savage. This goat-prophet was the principal occasion for Kant’s “Essay on the Maladies of the Head,” which appeared serially in the next five issues of the Königsbergsche Gelehrte und Politische Zeitungen.

Maladies of the Head [translations]

(anon.) “Versuch über die Krankheiten des Kopfes.” Königsbergsche Gelehrte und Politische Zeitungen, ##4-8, 13-27 February 1764. [AA 2: 259-71] “Essay on the Maladies of the Head.” Edited by Günter Zöller, translated by Holly Wilson in Zöller/Louden [2007, 65-77].

The occasion for this essay is explained in the previous item (see). Borowski offers the following: “This concerns a half-crazed fanatic [halbverrückten Schwärmer] who at that time lived in the vicinity of Königsberg – he travelled around with a cheerful youth and a herd of goats – and was always reciting Bible passages, especially from the prophets, for which reason he was called the ‘Goat-Prophet’ by the crowd of gaping onlookers.” Kant wrote in Maladies of the Head:

“This fanatic is in fact deranged from a supposed immediate inspiration, and a great familiarity, with the powers of heaven. Human nature knows no more dangerous illusion.” [AA 2: 267] German: Dieser ist eigentlich ein Verrückter von einer vermeinten unmittelbaren Eingebung und einer großen Vertraulichkeit mit den Mächten des Himmels. Die menschliche Nature kennt kein gefährlicheres Blendwerk.

Kant distinguishes three basic forms of mental illness: derangement (Verrückung) is a disturbance of the concepts of experience [AA 2: 264-65], madness (Wahnsinn) is a disorder of judgment (2: 265-68), and insanity (Wahnwitz) is a disorder of reason regarding more general judgements (2: 268-69).

Reprinted in Rink [1800, 34-55], Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 34-55].

Silberschlag [translations]

(anon.) “Rezension von Silberschlags Schrift: Theorie der am 23. Juli 1762 erschienenen Feuerkugel.” Königsbergsche Gelehrte und Politische Zeitungen, #15, 23 March 1764. [AA 8: 449-50; 2nd ed (1912): 2: 272d-e] “Review of Silberschlag’s Work: Theory of the Fireball that Appeared on July 23, 1762.” Translated by Eric Watkins in Watkins [2012, 411-13].

Kant’s authorship is confirmed in J.G. Hamann’s [bio] letter to J.G. Lindner [bio] (16 Mar 1764) [Briefwechsel, 2: 246].

Hamann [bio] was editor of Kanter’s newspaper at the time; in a passage mentioning pieces by F. S. Bock [bio] (on the Saturgus natural history cabinet [glossary]), and Funk [bio] (on Piper’s Markenrecht), we find this:

“Kants Recension von Silberschlags Erklärung der vor einigen Jahren erschienenen Sonnenkugel ist das letzte Stück von ihm und kommt vielleicht im nächsten Stück, mit einem lateinischen Gedicht des seel. Trib. R. v. Werner auf den Fruhling von Lauson eingeschickt. – Kanters Schwester wird heute beerdigt. […]”'

Prize Essay [translations]

“Untersuchung über die Deutlichkeit der Grundsätze der natürlichen Theologie und der Moral.” Abhandlung über die Evidenz in metaphysischen Wissenschaften (Berlin: Haude and Spener, 1764), pp. 67-99. [AA 2: 275-301] “Inquiry concerning the Distinctness of the Principles of Natural Theology and Morality.” Translated by David Walford and Ralf Meerbote in Walford [1992, 247-75].

Written near the end of 1762 in response to the question announced (on 23 June 1761) by the Royal Academy of Sciences in Berlin for the year 1763. The winners were announced on 31 May 1763, and Kant’s second-place essay – which opposed Wolffian rationalism by claiming that the methods of mathematics and philosophy were wholly different – was published by the Academy at the end of April 1764, alongside Moses Mendelssohn’s winning Wolffian essay. Following their translation of Kant’s essay, Walford and Meerbote also translate a 1763 summary of Mendelssohn’s essay (Ibid., pp. 276-86). (See a brief list of Academy prize questions.)

The Academy question was “whether the metaphysical truths in general, and the first principles of natural theology and morality in particular, admit of distinct proofs to the same degree as geometrical truths; and if they are not capable of such proofs, one wishes to know what the genuine nature of their certainty is, to what degree the said certainty can be brought, and whether this degree is sufficient for complete conviction” (as qtd. in Walford/Meerbote, p. lxii).

Kant’s answer was that metaphysics cannot successfully use the same method of mathematics (thus directly contradicting the position of the prize winning essay by Mendelssohn). Mathematics is successful not by analyzing concepts to arrive at new truths, but by constructing its objects from its own definitions. Metaphysics, on the other hand, deals with an independent reality, and so cannot proceed in this same fashion. Instead, the philosopher must begin with certain central concepts, like substance or obligation, and from these seek their definitions.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 2: 1-54].

1765

Announcement [translations]

“Nachricht von der Einrichtung seiner Vorlesungen in dem Winterhalbenjahre von 1765-1766” (Königsberg: Johann Jakob Kanter, 1765), 16 pp. [AA 2: 305-13] “Announcement of the Programme of his Lectures for the Winter Semester 1765-1766.” Translated by David Walford and Ralf Meerbote in Walford [1992, 291-300].

Lecture announcement for WS 1765/66.

Reprinted in Rink [1800, 56-70], Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 56-70].

1766

Dreams of a Spirit-Seer [translations]

(anon.) Träume eines Geistersehers, erläutert durch Träume der Metaphysik (Königsberg: Johann Jakob Kanter, 1766), 128 pp. [AA 2: 317-73] “Dreams of a Spirit-Seer Elucidated by Dreams of Metaphysics.” Translated by David Walford and Ralf Meerbote in Walford [1992, 305-59].

The publisher Kanter submitted the published book to the university censor on 31 January 1766. This led Kanter being fined 10 rthl., since he had failed to submit the written manuscript for censoring prior to it being printed, as required. In his appeal to the Academic Senate, Kanter noted the difficulties of submitting a written manuscript, since it was nearly illegible, and because it had been sent to him (from Goldap, where Kant was vacationing), sheet by sheet, for typesetting – Kant also notes this sheet-by-sheet procedure in his letter to Mendelssohn [AA 10: 71] – such that the work, in its present form, hardly existed until after it was printed [Dietzsch 2003, 91, reading from the Academic Senate minutes]. Kant thus appears to have finished this work during Christmas break – which usually lasted the month of December – on the estate of Daniel Friedrich von Lossow, located near Goldap (or Goldapp; Polish: Gołdap), on the eastern border of Prussia and about 75 miles from Königsberg [Ibid.]. The work appeared anonymously, although Kant did not keep his authorship a secret, sending copies to Moses Mendelssohn and others in Berlin. Mendelssohn responded negatively to the writing (in a no longer extant letter to Kant and in a one-paragraph notice of the book in the Allgemeine deutsche Bibliothek [see]), and Kant’s reply of 8 April 1766 (#37, AA 10: 69-73; English translation in Zweig 1999, 89-92) offers helpful insights into his own understanding of that work.

Walford [1992, lxviii] notes that, apart from the above printing, which is considered the most reliable, this work was also printed twice more in 1766 by Johann Friedrich Hartknoch (Riga and Mitau), and in Tieftrunk [1799, 2: 247-346].

1768

Directions in Space [translations]

“Von dem ersten Grunde des Unterschieds der Gegenden im Raume.” Wochentliche Königsbergische Frag- und Anzeigungs-Nachrichten, ##6-8 (1768). [AA 2: 377-83] “Concerning the Ultimate Ground of the Differentiation of Directions in Space.” Translated by David Walford and Ralf Meerbote in Walford [1992, 365-72].

This brief essay, appearing serially in three successive issues of the local newspaper, appeared at a time when Kant was publishing very little. Philosophically, the essay marks Kant’s break with the Leibnizian account of space as relational. Kant notes that incongruent counterparts like right- and left-hand gloves, or screws threaded in opposite directions, have identical descriptions based on their internal relations; conceptually they are identical, but intuitively we know that they are not.

Reprinted in Rink [1800, 71-80], Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 71-80].

1770

Inaugural Dissertation [translations]

De mundi sensibilis atque intelligibilis forma et principiis (Königsberg: Johann Jakob Kanter, 1770), 38 pp. [AA 2: 387-419] “On the Form and Principles of the Sensible and the Intelligible World.” Translated by Lewis White Beck in Beck [1992, 121-57]; by David Walford and Ralf Meerbote in Walford [1992, 377-416].

This was Kant's third (and final) public Latin defense, which took place on 21 August 1770, his so-called disputatio pro loco [glossary], the public defense of an essay made upon assuming a new professorship; see the brief description in the Professors pages.

In contrast to Leibniz and Wolff, who understood representations as all having the same source, being distinguished simply in terms of their clarity and distinctness, Kant argued here that human cognition is of two sorts, sensible and intellectual, and that these are wholly separate: sensible cognition cannot come from the intellect, and vice versa. Cognition of the spatio-temporal world is all sensible, cognition of what is eternal and unchanging is intellectual.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 2: 435-88], followed by a German translation prepared by Tieftrunk Tieftrunk [1799, 2: 489-566].

1771

Review of Moscati [translations]

(anon.) “Rezension zu Peter Moscati, Von dem körperlichen wesentlichen Unterschiede zwischen der Struktur der Tiere und Menschen.” Königsbergsche Gelehrte und Politische Zeitungen, #67, pp. 265-6 (23 August 1771). [AA 2: 423-25] “Review of Moscati’s Work: Of the Corporeal Essential Differences between the Structure of Animals and Humans.” Edited and translated by Günter Zöller in Zöller/Louden [2007, 79-81].

This is a review of Johann Beckmann’s German translation (Göttingen, 1771), 100 pp., of Delle corporee differenze essenziali che passano fra la struttura de' bruti, e la umana (Milan, 1770). Moscati (1739-1824), Some sources give 1736 as his birth year. who was born and died in Milan, enjoyed a career as a surgeon and politician, and between 1763 and 1772 taught as a professor of anatomy at the nearby university in Pavia.

Kant’s authorship was attested by his younger colleague, Jacob Christian Kraus, in his notes to Wald’s memorial speech given on April 23, 1804, reprinted by Reicke [Reicke 1860; Kraus’s comments on p. 17], who includes the review at the end of his reprint of Wald's speech and the collected materials (pp. 66-68).

1775

Races of Human Beings [translations]

Von den verschiedenen Racen der Menschen, zur Ankündigung der Vorlesungen der physischen Geographie im Sommerhalbjahr 1775 (Königsberg: Hartung, 1775), 12 pp. [AA 2: 429-43] “Of the Different Races of Human Beings, and to announce the lectures on physical geography for the summer semester 1775.” Translated by Jon Mark Mikkelsen in Mikkelsen [2013, 41-54, 55-71] – both the 1775 lecture announcement and the 1777 revised essay. Edited by Günter Zöller, translated by Holly Wilson and Günter Zöller in Zöller/Louden [2007, 84-97].

A lecture announcement for SS 1775, and the last of the seven that we have from Kant. A new edition of this essay was printed in J. J. Engel, Der Philosoph für die Welt (Leipzig, 1777), 2: 125-64 [PDF]. Engel omits the first and last paragraphs, in which the lectures for the semester are mentioned. This 2nd edition text, with the opening and closing paragraphs restored, is used for the Academy Edition and serves as the basis of the Wilson/Zöller translation.

Wilson/Zöller note in their introduction to their translation [2007, 83]:

“Following the Academy edition, the translation provides the text of the second, revised edition, augmented by the opening paragraph and the closing paragraph of the first edition. The original versions of the passages that were changed in the second edition, which are recorded in the Academy edition, have been omitted.”

The Weischedel edition [1968; 11: 11-30] footnotes all the changes made in the second edition, while the Academy edition provides these as “Lesarten” near the end of the volume [AA 2: 519-22].

Kant argues that there is a single human species, and that this is divided into four races distinguished primarily by skin color (white, red, black, yellow). Although these races are stable across generations, they were originally differentiated as a result of climate. The racial characteristics are reliably passed down from one generation to the next, and the mixing of races similarly result in a mixing of the racial phenotypes. This topic was originally addressed in the Physical Geography lectures, and then later in the Anthropology lectures. The nature of the human species is also discussed in his Concept of Race (1785) and his Teleological Principles (1788).

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 2: 607-32].

1776-77

Philanthropinum [translations]

(anon.) “Zwei Aufsätze, betreffend das Basedow’sche Philanthropinum.” Königsbergsche Gelehrte und Politische Zeitungen, 28 March 1776 and 27 March 1777. [AA 2: 447-52] “Essays Regarding the Philanthropinum.” Edited and translated by Robert Louden in Zöller/Louden [2007, 100-104].

See Kant’s letters of 28 March 1776 to Christian Heinrich Wolke, the director of the Philanthropin school in Dessau (#109, AA 10: 191-94) See also a second letter to Wolke, dated 4 August 1778 (#138, AA 10: 236), written shortly after the letter to Wilhelm Crichton. Crichton (1732-1805) was a local pastor and editor at Kanter’s KGPZ; Kant’s letter to him was published in Tieftrunk’s 1807 Kant’s Vermischte Schriften (pp. 420-24), to which Tieftrunk appends several long annotations.

Kant’s authorship is also attested by his younger colleague, Jacob Christian Kraus, in his notes to Wald’s memorial speech given on April 23, 1804, reprinted by Reicke [Reicke 1860; Kraus’s comments on p. 17], who includes the review at the end of his reprint of Wald's speech and the collected materials (pp. 68-81). – Kant enclosed a copy of his KGPZ article with the letter – and of 19 June 1776 to Johann Bernhard Basedow, who founded the school (#110, AA 10: 194-95). The following spring, near the publication of the second essay, we find Kant still working on the school’s behalf in correspondence with Friedrich Wilhelm Regge (22 March 1777, #114; AA 10: 201) and Joachim Heinrich Campe (two letters: 26 August 177, #121, AA 10: 214, and 31 October 1777, #122, AA 10: 216), and again in a letter of 29 July 1778 to Wilhelm Crichton (#136, AA 10: 234-35). Kant had also worked to procure his student (and future colleague) Christian Jacob Kraus a position there [Krause 1881, 62]. This interest in the Philanthropinum is echoed in the Friedländer anthropology notes (dated to WS 1775/76), which end with a discussion “on education” [AA 25: 722-28].

Given the urgency Kant felt to finish the Critique of Pure Reason, the amount of time he devoted to the support of this experimental school is quite remarkable.

1777

Sensory Illusion [translations]

“Concerning Sensory Illusion and Poetic Fiction.” Published posthumously: Arthur Warda, Altpreussische Monatsschrift, 47 (1910), 662-70. Translated into German by Bernhard Adolf Schmidt and published in Kant-Studien 16 (1911), 5-21. [AA 15: 903-35, printed as Refl. #1525] Translated into English by Ralf Meerbote in Beck [1992, 169-83].

This was an untitled Latin commentary provided at the inaugural dissertation (the disputatio pro loco [glossary]) of the new professor of poetry, Johann Gottlieb Kreutzfeld [bio], on 28 February 1777. Kant wrote this on his bound, interleaved copy of Kreutzfeld’s published disputation: Dissertatio philologico poetica de principiis fictionum generalioribus (Königsberg, 1777), 26 pp. – available online (courtesty Universitas Tartuensis). On the manuscript and its discovery, see Stolovich [2011, 80-83].

1781

Critique of Pure Reason [translations]

Critik der reinen Vernunft (Riga: Johann Friedrich Hartknoch, 1781) [(4)(16)(2) 856 p.] 2nd (B) ed: 1787 [xliv, 884 p.] [A-edition (AA 4: 5-252); B-edition (AA 3: 2-552). “Critique of Pure Reason.” Translated by Norman Kemp Smith in Kemp Smith [1929]; by Werner Pluhar in Pluhar [1996]; by Paul Guyer and Allen W. Wood in Guyer/Wood [1998].

“In the current Easter book fair there will appear a book of mine, entitled Critique of Pure Reason […] This book contains the result of all the varied investigations that start from the concepts we debated together under the heading mundi sensibilis and mundi intelligibilis.” – thus begins Kant’s letter to Marcus Herz from 1 May 1781 [AA 10: 266].

Kant’s own copy of this book was housed at the Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Königsberg, before being lost in 1945. Fortunately Kant’s marginalia had already been printed in Erdmann [1881; reprinted at AA 23: 17-50] and are also included in the Guyer/Wood translation.

In a letter to Biester (8 June 1781), Kant wrote that “though this book has occupied my thinking for a number of years, I have put it down on paper in its present form in only a short time” [AA 10: 272]. See Kant’s brief synopsis of this work in his letter to Moses Mendelssohn [16 Aug 1783; AA 10: 345-46].

1782

Lambert’s Letters [translations]

(anon.) “Anzeige von Joh. Bernoullis Ausgabe des Lambertischen Briefwechsels.” Königsbergsche Gelehrte und Politische Zeitungen, #10, 4 February 1782. [AA 8: 3-4] “A Notice of Johann Bernoulli’s Edition of Lambert’s Correspondence.” Translated by Eric Watkins in Watkins [2012, 415-17].

Johann Bernoulli’s (1744-1807) edition of the Lambert correspondence appeared between 1782 and 1785. He had visited Königsberg in 1778 (June 29-July 2), making Kant’s acquaintance at that time. [more] Bernoulli's letters to Kant have gone missing, but we have two letters from Kant: 16 November 1781 (#172, AA 10: 276-78) and 22 February 1782 (#174, AA 10: 280-81). In the former, Kant apologizes for not being able to locate (or have saved) some of his correspondence with Lambert; in the latter, he thanks Bernoulli for the volume of correspondence, and mentions the above notice that he had published. See also Kant’s letter to G. C. Reccard [bio] (7 June 1781; #167, AA 10: 270-71).

Note to Physicians [translations]

“Nachricht an Ärzte.” Königsbergsche Gelehrte und Politische Zeitungen, #31, 18 April 1782. [AA 8: 6-8] “A Note to Physicians.” Edited and translated by Günter Zöller in Zöller/Louden [2007, 106].

This concerns the influenza epidemic of 1782, and consists of a reprint of an article by a Dr. John Fothergill, originally printed in Gentleman’s Magazine (February 1776) and translated into German by Kant’s colleague C. J. Kraus [bio], with a signed introductory paragraph by Kant. See Kraus’s brief letter to Kant from April 1782 [AA 10: 282], which also indicates that Joseph Green was the source for the copy of the Gentleman’s Magazine.

Kant was interested in the physico-geographical aspects of this illness, how it was able to spread around the globe by means of ships and trade caravans. Kant’s colleague, the professor of medicine J. D. Metzger [bio], published a work on this epidemic: Beytrag zur Geschichte der Frühlings-Epidemie im Jahr 1782 (Königsberg & Leipzig, 1782).

1783

Prolegomena [translations]

Prolegomena zu einer jeden künftigen Metaphysic, die als Wissenschaft wird auftreten können (Riga: F. J. Hartknoch, 1783), 222 pp. [AA 4: 255-383] “Prolegomena to any Future Metaphysics that will be able to come forward as a Science.” Translated by Lewis White Beck in Beck [1950]; by James W. Ellington in Ellington [1977]; by Gary Hatfield in Allison/Heath [2002, 51-169].

The Prolegomena was intended as a brief introduction to the new critical philosophy that Kant had developed in his Critique of Pure Reason (1781), and the idea to write this occurred not long after the Critique was published (see Kant’s letter to Herz of 11 May 1781 [AA 10: 269]), although its tone and content shifted in response to the Garve/Feder review (published 19 January 1782).

Review of Schulz [translations]

“Rezension von Schulz, Versuch einer Anleitung zur Sittenlehre für alle Menschen, ohne Unterschied der Religion, nebst einem Anhange von den Todesstrafen.” Räsonnirendes Bücherverzeichnis (Königsberg: Hartung, 1783), pp. 97-100.

Warda [1919, 30] reads: “Raisonnirendes / Verzeichniß neuer Bücher. / No. VII. / April 1783. / 8°.” Goldbeck [1783, 226] described this periodical as follows:

Raisonnirendes Verzeichniß neuer Bücher. Eine Art von monatlicher gelehrter Zeitung, wovon seit dem Anfange des J. 1782 in der Hartungschen Buchhandlung zu Königsberg monatlich ein Stück von einem bis anderthalb Bogen in gr. 8° auf schönem weissen Papier mit kleinen Lettern sehr enge gedruckt herauskommt. Die Verf. der Anzeigen sind größtentheils Königsbergische oder doch Preussische Gelehrte.”

[AA 8: 10-14] “Review of Johann Heinrich Schulz’s Essay on the Moral Instruction of all Humans, regardless of their Religion.” Translated by Mary J. Gregor in Gregor [1996, 7-10].

Johann Heinrich (“Pony-tail Schulz”) Schulz [bio] was a Lutheran pastor arguing against human freedom. His book was published anonymously.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 371-78].

1784

Universal History [translations]

“Idee zu einer allgemeinen Geschichte in weltbürgerlicher Absicht.” Berlinische Monatsschrift (November 1784), vol. 4, pp. 385-411. [AA 8: 17-31] “Idea for a Universal History with a Cosmopolitan Aim.” Translated by Ted Humphrey in Humphrey [1983a, 29-39]. Edited by Günter Zöller, translated by Allen W. Wood in Zöller/Louden [2007, 108-20].

This was the lead article for the November 1784 issue.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 2: 661-86].

Enlightenment [translations]

“Beantwortung der Frage: Was ist Aufklärung?” Berlinische Monatsschrift (December 1784), vol. 4, pp. 481-94. [AA 8: 35-42] “An Answer to the Question: What is Enlightenment?” Translated by Ted Humphrey in Humphrey [1983a, 41-46]; by Mary J. Gregor in Gregor [1996, 17-22].

J. F. Zöllner [bio] published an article in the December 1783 issue of the Berlinische Monatsschrift in which he opposed the institution of civil marriage – an idea suggested in an article anonymously written by the journal’s editor, J. E. Biester [bio], for the previous September issue and which claimed that tying marriage to religion was contrary to Enlightenment ideals. Zöllner countered that marriage was too important an institution for this and required a stability that only religion could provide. The very foundations of morality were being shaken, Zöllner wrote, and we should rethink our steps before “confusing the hearts and minds of the people in the name of Enlightenment” – at which point he asked in a footnote: “What is enlightenment? This question, which is nearly as important as ‘What is truth?’ should be answered before one begins to enlighten.”

Zöllner’s question led to a series of essays appearing in the Berlinische Monatsschrift and elsewhere, most famously Kant’s, the lead article for the December 1784 issue. An essay by Moses Mendelssohn (“On the Question: What is Enlightenment?”) was first delivered as a speech (16 May 1784) before the “Wednesday Society” to which he, Zöllner, Biester, and other leading figures of the Berlin Enlightenment belonged.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 2: 687-700].

1785

Review of Herder 1 [translations]

(anon.) “Rezension zu Johann Gottfried Herder, Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit (Erster Teil)” in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, #4, 6 January 1785, vol. 1, pp. 17-20 + Appendix to #4, pp. 21-22. [AA 8: 45-55] “Review of Herder, Ideas for the Philosophy of the History of Humanity.” Translated by H. B. Nisbet in Reiss [1991, 201-20]. Edited by Günter Zöller, translated by Allen W. Wood in Zöller/Louden [2007, 124-42].

Christian Gottfried Schütz [bio] wrote to Kant on 10 July 1784 [AA 10: 392-94], inviting him to contribute to a new journal that he was planning, and hoping that Kant might begin with a review of Herder’s Ideen; Kant agreed, and his review appeared in the journal’s first week (issue #4). Schütz wrote again on 18 February 1785:

“You have probably seen a copy of your review of Herder [bio] by now. Everyone who has read it with impartial eyes thinks it a masterpiece of precision and – are you suprised? – many readers recognized that you must be the author. I can tell you that this review, since it came out in the trial issue of the journal, has certainly accounted for much of the favorable response to the A.L.Z.. They say that Herr Herder is very sensitive to the review. A young convert by the name of Reinhold [bio] who is staying in Wieland’s house in Weimar and who has already sounded an abominable fanfare in the Merkur about Herder’s piece intends to publish a refutation of your review in the February issue of that journal.” [AA 10: 398]

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 383-414 – this includes all three reviews of Herder].

Review of Herder 2 [translations]

(anon.) “Errinerungen des Rezensenten der Herderschen Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit über ein im Februar des Teutschen Merkur gegen diese Rezension gerichtetes Schreiben” in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, Appendix to the March issue (2 pp., unpaginated). [AA 8: 56-58]

See the note to Herder 1, above. The essay countering Kant’s earlier review of Herder was published anonymously in the Teutsche Merkur. K. L. Reinhold [bio] later claimed responsibility for the essay (in a letter to Kant, 12 October 1787; #305, AA 10: 497-500), although Kant was already aware of Reinhold’s identity from Schütz’s letter (as quoted above).

Review of Herder 3 [translations]

(anon.) “Rezension zu Johann Gottfried Herder, Ideen zur Philosophie der Geschichte der Menschheit (Zweiter Teil)” in the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, #271, 15 November 1785, vol. 3, pp. 153-56. [AA 8: 58-66]

See the note to Herder 1, above. This is Kant’s review of Part Two of Herder’s Ideen, which he appears to have written in early November 1785, as Hamann suggests in a letter to Scheffner (6 November 1785) [Briefwechsel, 6: 123]. Kant declined to review Part Three when it appeared, since he was needing time to begin work on “the foundation of the critique of taste“ (letter to Schütz, 25 June 1787; #300, AA 10: 489-90).

Volcanoes [translations]

“Über die Vulkane im Monde.” Berlinische Monatsschrift (March 1785), pp. 199-213. [AA 8: 69-76] “On the Volcanoes on the Moon.” Translated by Olaf Reinhardt in Watkins [2012, 419-25].

This and the following essay were sent to J. E. Biester [bio] with a letter dated 31 December 1784 (#236; AA 10: 397).

Kant is responding in this essay to a recent proposal that the craters seen on the moon are large volcanoes. He notes that there are two kinds of crater-like formations on the earth: one, of volcanic origin, and a second that is non-volcanic, and with an area roughly 200,000 larger. It is only this second kind, however, that would be visible, were we to look at the earth with our telescopes. Thus, the observed moon-craters are more likely not to be volcanic. Kant suggests an origin based on his Natural History (1755).

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 3: 1-16].

Groundwork [translations]

Grundlegung zur Metaphysik der Sitten (Riga: Johann Friedrich Hartknoch, 1785), xiv, 128 pp.; 2nd edition: 1786. [AA 4: 387-463] “Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals.” Translated by Lewis White Beck in Beck [1949, pp-pp]; by James Ellington in Ellington [1981]; by Mary J. Gregor in Gregor [1996, 43-108].

The academy edition is based on the 2nd edition (1786). 3rd ed. (1792), 4th ed. (1797) [AA 4: 630].

Kant mentions in his first letter to J. H. Lambert (31 December 1765) that he was preparing a “metaphysical groundwork of practical philosophy” (alongside a “metaphysical groundwork of natural philosophy”) [AA 10: 56]. Nearly two decades latter, in a letter of 11 Jan 1782, J. G. Hamann writes to the publisher Hartknoch that “Kant is working on the Metaphysics of Morals – I don’t know for which publisher. He thinks he will be finished with the little text around Easter.” Two and a half years later, in September 1784, Kant’s amanuensis J. B. Jachmann was busily writing a clean copy for the publisher in August 1784 (Hamann’s letter to Harknoch, 10 August 1784 [Briefwechsel, 1955-79, 5: 182]) and a month later the manuscript was sent off (Hamann’s letter to Scheffner, 19/20 Sep 1784 [5: 222]). Kant sent this manuscript to Hartknoch and the published book appeared at the 1785 Easter book fair.

Kant mentions in a letter to Moses Mendelssohn [16 Aug 1783; AA 10: 346]: “This winter I shall have the first part of my [book on] moral [philosophy] substantially completed. This work is more adapted to popular tastes, though it seems to me far less of a stimulus to broadening people’s minds than my other work is, since the latter tries to define the limits and the total content of the whole of human reason.”

This is Kant’s first, relatively brief, best known, and most closely studied text on moral philosophy, in which he develops the concept of the categorical imperative and establishes the autonomy of the will as the grounding principle of morality. The Feyerabend notes stem from Kant’s 1784 lectures on natural law, and offer insights into the Groundwork. Henrich claims, in light of Kant’s writings from the 1760s, that "there can be no more doubt that the Grou,dwork of the Metaphysics of Morals that finally appeared twenty years [after his letter to Lambert] was a continuation of that original plan.” [Henrich 1963, 404].

Counterfeiting Books [translations]

“Von der Unrechtmäßigkeit des Büchernachdrucks.” Berlinische Monatsschrift (May 1785), pp. 403-17. [AA 8: 79-87] “On the Wrongfulness of Unauthorized Publication of Books.” Translated by Mary J. Gregor in Gregor [1996, 29-35].

Book pirating was already being widely discussed when Kant’s article appeared. After its initial publication in the Berlinische Monatsschrift, it was next reprinted in a pirated collection of Kant’s essays: Zerstreute Aufsätze (Frunkfurt/Leipzig, 1793), pp. 50-64.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 3: 17-32].

Concept of Race [translations]

“Bestimmung des Begriffs einer Menschenrasse.” Berlinische Monatsschrift (November 1785), pp. 390-417. [AA 8: 91-106] “Determination of the Concept of a Human Race.” Translated by Jon Mark Mikkelsen in Mikkelsen [2013, 125-41]. Edited by Günter Zöller, translated by Holly Wilson and Günter Zöller in Zöller/Louden [2007, 145-59].

The concept of human races is also discussed in his Races of Human Beings (1775) and his Teleological Principles (1788).

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 2: 633-60].

1786

Conjectural Beginning [translations]

“Mutmaßlicher Anfang der Menschengeschichte.” Berlinische Monatsschrift (January 1786), pp. 1-27. [AA 8: 109-23] “Conjectural Beginning of Human History.” Translated by Ted Humphrey in Humphrey [1983a, 49-59]; by H. B. Nisbet in Reiss [1991, 221-34]. Edited by Günter Zöller, translated by Allen W. Wood in Zöller/Louden [2007, 163-75].

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 3: 33-60].

Metaphysical Foundations [translations]

Metaphysische Anfangsgründe der Naturwissenschaften (Riga: Johann Friedrich Hartknoch, 1786), xxiv, 158 pp. (2nd printing: 1787; 3rd printing: 1800). [AA 4: 467-565] “Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science.” Translated by James W. Ellington in Ellington [1970]; by Michael Friedman in Allison/Heath [2002, 171-270], slightly revised in Friedman [2004].

Kant reports finishing this in the summer of 1785 (letter to C. G. Schütz, 13 Sep 1785; #243, AA 10: 405-7):

“So I finished them this summer, under the title Metaphysical Foundations of Natural Science, and I think the book will be welcomed even by mathematicians. It would have been published this Michaelmas, if I hadn't injured my right hand and been prevented from writing the ending. The manuscript must now lie till Easter. Now I am proceeding immediately with the full composition of the Metaphysics of Morals […]” [AA 10: 406; Zweig transl.]

See also Hamann’s 18 Aug 1785 letter to Herder [Briefwechsel, 6: 55].

Hamann [Briefwechsel, 6: 55]:

“[Kant] has had the misfortune of paralysing his right hand, so that he is apparently unable to write, for which he has the most leisure during the dog-day holidays, especially now that his Metaphysics of Bodies is to appear at Michaelmas.”

[“Er hat das Unglück gehabt sich seine rechte Hand zu verlähmen, daß er nicht im stande seyn soll die Feder zu führen, wozu er währender Hundstagferien die beste Muße hat, besonders da seine Metaphysik der Körper auf Michaelis erscheinen soll”]

Summer semester classes would run another month (the last physical geography lecture was September 17, a Saturday) and the winter term would not begin until October 10. Kant served as the Philosophy Dean during the 1785-86 semester, but his duties would not have begun until the beginning of that term.

Review of Hufeland [translations]

“Rezension von Gottlieb Hufeland, Versuch über den Grundsatz des Naturrechts.” Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, #92, 18 April 1786, cols. 113-16. [AA 8: 127-30] “Review of Gottlieb Hufeland’s Essay on the Principle of Natural Right.” Translated by Allen W. Wood in Gregor [1996, 115-17].

Gottlieb Hufeland [bio] was at the time a young lecturer in law and moral philosophy at Jena.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1807, 4: 414-19].

Orientation in Thinking [translations]

“Was heißt: sich im Denken orientieren?” Berlinische Monatsschrift (October 1786), pp. 304-30. [AA 8: 133-47] “What does it mean to orient oneself in thinking?” Translated by H. B. Nisbet in Reiss [1991, 237-49]; by Allen W. Wood in Wood/di Giovanni [1996, 7-18].

Written in late summer/early fall of 1786, not long after the death of Friedrich II (Hamann’s letter to Jacobi, section dated 12 July 1786: “Kant schreibt über das Mendelssohnische Orientiren”).

This was Kant’s long awaited entry into the Pantheismusstreit between Jacobi and Mendelssohn. Both sides had anticipated Kant’s defense, and he disappointed them both by rejecting Jacobi’s sentimentalist faith (“leap of faith”) as well as Mendelssohn’s rationalist faith (as exemplified in his Morgenstunden, in which proofs of God’s existence were defended as successful – a form of dogmatism), viewing them both as leading to fanaticism. The proper function of reason was to free concepts from contradictions and to defend the “maxims of sound reason” from the “sophistical attacks of speculations.”

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 3: 61-88].

Remarks on Jakob [translations]

“Einige Bemerkungen” on Ludwig Heinrich Jakob, Prüfung der Mendelssohnschen Morgenstunden (Leipzig: Heinsius, 1786), pp. li-lx. [AA 8: 151-55] “Some Remarks on L. H. Jakob’s Examination of Mendelssohn’s Morgenstunden.” Translated by Günter Zöller in Zöller/Louden [2007, 178-81].

Jakob [bio] taught philosophy at Halle. Kant’s remarks were printed as a preface to Jakob’s book.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 3: 89-98].

1787

Critique of Pure Reason (2nd edition) [translations]

See entry for the 1st edition.

In a letter to Johann Bering [bio] (7 April 1786, #266), Kant discusses his “new, highly revised edition of my Critique, which will come out soon, perhaps within half a year; […] I shall not change any of its essentials, since I thought out these ideas long enough before I put them on paper and, since then, have repeatedly examined and tested every proposition belonging to the system and found that each one stood the test, both by itself and in relation to the whole” [AA 10: 441; transl. Zweig 1999, 249].

A brief notice in the Tuesday, 21 November 1786 (vol. 4, col. 359), issue of the Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung claims the new edition will be available at the following Easter book fair, and that it will include a “Critique of Pure Practical Reason” [see]; this material was later removed, amplified, and published separately in 1788.

Hamann’s letter (30 Jan 1787) to F. H. Jacobi notes that Kant sent his manuscript to the publisher at the beginning of the month [Briefwechsel, 7: 104-5].

1788

Critique of Practical Reason [translations]

Critik der practischen Vernunft (Riga: Johann Friedrich Hartknoch, 1788), 292 pp. [AA 5: 1-164] “Critique of Practical Reason.” Translated by Lewis White Beck in Beck [1949, pp-pp]. Translated by Mary J. Gregor in Gregor [1996, 139-271]; by Werner S. Pluhar in Pluhar [2002].

Kant sent the manuscript to the printers (Grünert, in Halle) in summer 1787 (letter to C. G. Schütz, 25 June 1787: “I intend to send it to Halle for printing next week” [AA 10: 490]; letter to L. H. Jakob, 11 September 1787: “My Critique of Practical Reason is at Grunert’s now” [AA 10: 494].

Kant’s own 1st edition copy of this book, originally given to Wasianski [bio] as a gift, Vaihinger traces the ownership from Kant to Wasianski, Buck, Crüger, and Schopenhauer (as a loaner)[1898e, 389-90]. Kant left what was left of his library to his younger colleague J. F. Gensichen [bio], who apparently was not aware of this gift, as he reported to Wald [bio] that the books he inherited from Kant included none of his publications prior to 1781, nor the Critique of Practical Reason, noting only that Kant, in his later years, had given many of his books away as gifts [Reicke 1860, 56]. is available in Halle (at the university archive). Kant’s marginalia are not printed in the Academy edition, although they are mentioned in the Lesearten [AA 5: 500-5]. A set of facsimiles of Kant’s copy is available at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Sciences website.

Teleological Principles [translations]

“Über den Gebrauch teleologischer Principien in der Philosophie.” Teutscher Merkur (January and February 1788), pp. 36-52, 107-36. [AA 8: 157-84] “On the Use of Teleological Principles in Philosophy.” Translated by Jon Mark Mikkelsen in Mikkelsen [2013, 169-94]; by Günter Zöller in Zöller/Louden [2007, 195-218].

Kant completed this essay in December 1787, having sent it with a letter to K. L. Reinhold [bio] (28/31 December 1787; #313, AA 10: 513-16), who was helping his father in law, C. M. Wieland [bio], edit the Teutsche Merkur. As Kant explained in that letter, the essay had a double occasion and purpose: (1) to acknowledge the accuracy of Reinhold’s “Letters on the Kantian Philosophy” and (2) to respond to various criticisms raised by Georg Forster [bio] (in the Teutsche Merkur October and November 1786, pp. 57-86, 150-66) against Kant’s “Concept of Race” (1785) and “Conjectural Beginning” (1786). Reinhold had asked, in a letter introducing himself to Kant, for such an acknowledgement (12 October 1787; #305, AA 10: 497-500). This was Kant’s only publication in this journal.

Reprinted in Tieftrunk [1799, 3: 99-144].

Kraus Review [translations]

“Kraus’ Recension von Ulrich’s Eleutheriologie.” Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung, #100, cols. 177-84, 25 April 1788. [AA 8: 453-60] “Kraus’s Review of Ulrich’s Eleutheriologie.” Translated by Mary J. Gregor in Gregor [1996, 125-31].

C. J. Kraus [bio] wrote this review of Ulrich’s [bio] Eleutheriologie, oder über Freyheit und Nothwendigkeit [Eleutherology, or On Freedom and Necessity] (Jena: Cröker, 1788)[106 pp.] at Kant’s request and with his input (Kant’s own draft is printed at AA 23: 79-81). The history of this review, and Kant’s connection with it, is discussed in Stark [1987b, 171-3]. Vaihinger [1880] was the first to publish a transcript of Kant’s notes, and also attempted there to sort-out the extent to which Kraus made use of it in his review. (Hamann’s letter of 27 April 1787 to Jacobi mentions Kant’s displeasure with Kraus’s draft [Briefwechsel, 7: 164].)

Three years earlier Ulrich had sent Kant a copy of his Institutiones logicae et metaphysicae (Jena, 1785), and C. G. Schütz [bio], editor of the A.L.Z., hoped that Kant would review it and, if not Kant, then perhaps his colleague Johann Schultz [bio]. Schultz published his review 13 December 1785.

Philosophers’ Medicine [translations]

“On Philosophers’ Medicine of the Body” (“De medicina corporis, quae philosophorum est”). Published posthumously: Johannes Reicke, “Kant’s Rede ‘De medicina corporis, quae philosophorum est’,” Altpreussische Monatsschrift, 18 (1881), pp. 293-309, and published separately as Immanuel Kant, Rede de medicina corporis, quae philosophorum est (Königsberg: Beyer, 1881), 19 pp. [AA 15: 939-53, printed as Refl. #1526] “On the Philosophers’ Medicine of the Body.” Translated by Mary J. Gregor in Beck [1992, 228-43] and in Zöller/Louden [2007, 184-91].

The original manuscript in Kant’s hand – a folded sheet, resulting in four pages of text – was in the possession of Rudolf Reicke at the time of its publication. Dating is uncertain; the text was given as an address at the completion of a term as the university rector, a role that Kant filled twice [more]: SS 1786 and SS 1788, so the address would have been given either 1 Oct 1786 or 5 Oct 1788 – the installation of the new rectors occurred on the first Sunday after St. Michael (September 29) for winter semester, and the first Sunday after Easter, for summer semester. Gregor precedes her translation in the Beck edition with a detailed introduction (pp. 217-27).

1789

First Introduction [translations]

“Erste Fassung der Einleitung in die Kritik der Urteilskraft.” Partial publication by Kant’s student, J. S. Beck [bio], at the end of the second volume of his Erläuternder Auszug aus den critischen Schriften des Herrn Prof. Kant, auf Anrathen desselben (Riga: Hartknoch, 1794).

Beck published a little over half of the manuscript, omitting some paragraphs and footnotes, as well as sections 2, 7, 9, 12, and most of 4 (of the 12 sections). This shortened version was then reproduced in F. Ch. Starke [bio] (Immanuel Kant's vorzügliche kleine Schriften und Aufsätze, Quedlinburg/Leipzig, 1833, 2: 223-62) with the title “Ueber Philosophie überhaupt”.

This text and title were further reprinted in Hartenstein’s 10-volume edition of Kant’s writings (1838, 1: 137-72), in the Rosenkranz/Schubert 12-volume edition of Kant’s writings (1838, 1: 579-617), in Hartenstein’s 8-volume chronologically arranged edition of Kant’s writings (1868, 6: 373-404) – although the 1868 edition of Hartenstein adds the useful sub-title: “zur Einleitung in die Kritik der Urtheilskraft”. Eisler [1924, 641] also includes this in his bibliography of Kant’s writings: “Über Philosophie überhaupt, 1794”. '1794' is the publication date of the Beck volume.

First publication of the manuscript in full was in vol. 5 (1914) of the Cassirer edition of Immanuel Kants Werke (Berlin: 1912-22), 11 vols. [AA 20: 195-251]

A facsimile of the manuscript and transcription can be found in Hinske, et al. [1965], which also includes a helpful history.

“First Introduction to the Critique of the Power of Judgment.” Translated by James Haden in Haden [1965]. Translated by Werner S. Pluhar in Pluhar [1987, 385-441]; by Paul Guyer and Eric Matthews in Guyer [2000, 3-51].