Robert Darnton on Spreading the Word

Information is exploding so furiously around us and information technology is changing at such bewildering speed that we face a fundamental problem: How to orient ourselves in the new landscape? What, for example, will become of research libraries in the face of technological marvels such as Google?

.jpg) Rosetta Stone

Rosetta Stone

196 BCE

(>>British Museum, London)

How to make sense of it all? I have no answer to that problem, but I can suggest an approach to it: look at the history of the ways information has been communicated. Simplifying things radically, you could say that there have been four fundamental changes in information technology since humans learned to speak.

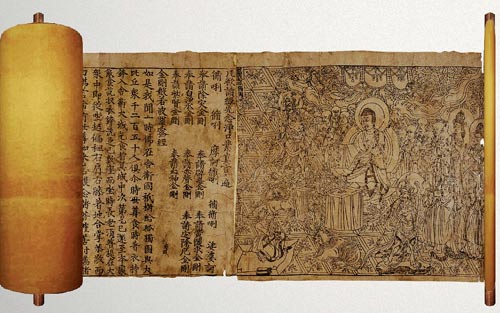

The Diamond Sutra

The Diamond Sutra

868 CE

Oldest printed text, on a scroll (>>British Library, London)

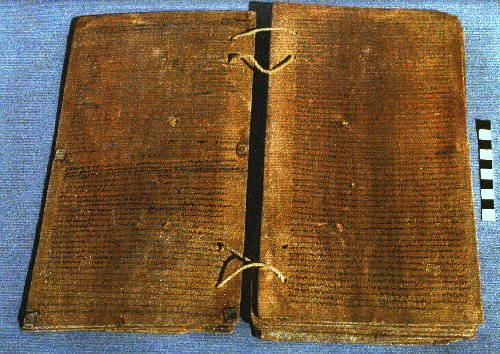

Somewhere, around 4000 BC, humans learned to write. Egyptian hieroglyphs go back to about 3200 BC, alphabetical writing to 1000 BC. According to scholars like Jack Goody, the invention of writing was the most important technological breakthrough in the history of humanity. It transformed mankind’s relation to the past and opened a way for the emergence of the book as a force in history.

The history of books led to a second technological shift when the codex replaced the scroll sometime soon after the beginning of the Christian era. By the third century AD, the codex — that is, books with pages that you turn as opposed to scrolls that you roll — became crucial to the spread of Christianity. It transformed the experience of reading: the page emerged as a unit of perception, and readers were able to leaf through a clearly articulated text, one that eventually included differentiated words (that is, words separated by spaces), paragraphs, and chapters, along with tables of contents, indexes, and other reader’s aids.

The codex, in turn, was transformed by the invention of printing with movable type in the 1450s. To be sure, the Chinese developed movable type around 1045 and the Koreans used metal characters rather than wooden blocks around 1230. But Gutenberg’s invention, unlike those of the Far East, spread like wildfire, bringing the book within the reach of ever-widening circles of readers. The technology of printing did not change for nearly four centuries, but the reading public grew larger and larger, thanks to improvements in literacy, education, and access to the printed word. Pamphlets and newspapers, printed by steam-driven presses on paper made from wood pulp rather than rags, extended the process of democratization so that a mass reading public came into existence during the second half of the nineteenth century.

The fourth great change, electronic communication, took place yesterday, or the day before, depending on how you measure it. The Internet dates from 1974, at least as a term. It developed from ARPANET, which went back to 1969, and from earlier experiments in communication among networks of computers. The Web began as a means of communication among physicists in 1981. Web sites and search engines became common in the mid-1990s. And from that point everyone knows the succession of brand names that have made electronic communication an everyday experience: Web browsers such as Netscape, Internet Explorer, and Safari, and search engines such as Yahoo and Google, the latter founded in 1998.

When strung out in this manner, the pace of change seems breathtaking: from writing to the codex, 4,300 years; from the codex to movable type, 1,150 years; from movable type to the Internet, 524 years; from the Internet to search engines, nineteen years; from search engines to Google’s algorithmic relevance ranking, seven years; and who knows what is just around the corner or coming out the pipeline?

[Excerpt from Robert Darnton, “The Library in the New Age” in The New York Review of Books (12 June 2008)

Robert Darnton, an American historian specializing in 18th century France, is the Carl H. Pforzheimer University Professor at Harvard (since 2007), having previously served as the Shelby Cullom Davis Professor of European History at Princeton University.